There was a lot of discussion at OpenEd17 about the relationship between OER and value-added services like platforms. The discussion was energized by an announcement made by Cengage immediately ahead of the conference, but this is a conversation that has been percolating for a while now.

Examples of Value-Added Services in the Context of Open

Both the wider internet and the narrower education space are filled with companies and organizations that provide value-added services around openly licensed software and content. A few examples include:

- Automattic provides a broad range of for-fee, value-added services around the open source WordPress software, including WordPress.com (hosting), WordPress.com VIP (hosting), Akismet (anti-spam), Jetpack (security), and many others.

- Pressbooks (Book Oven Inc. according to the receipt I received when I bought services from them for Project Management for Instructional Designers) provides a wide range of for-fee, value-added services based on the open source Pressbooks plugin for WordPress, including hosting, custom branding, support, and a premium PDF rendering engine.

- Reclaim Hosting offers for-fee, value-added services around open source web hosting and publishing software like Cpanel, Installatron, Apache, WordPress, Known, and Omeka.

- Carnegie Mellon’s Open Learning Initiative provides for-fee, value-added hosting and customer support services around openly licensed content.

- OpenStax provides a for-fee, value-added service called OpenStax Tutor around openly licensed content.

- Lumen provides for-fee, value-added hosting, integration, assessment, messaging, and other services around openly licensed content.

- Open Up Resources provides teacher training, professional development, and related for-fee, value-added services around openly licensed K-12 content.

- And of course, Instructure (Canvas), Moodle Pty Ltd (Moodle), Longsight (Sakai), and other companies provide for-fee, value-added services around Learning Management Systems hosting and support.

These and many other value-added services provided around open source software and open content (my apologies if I omitted your service from my list) are critically important in the education context for at least two reasons.

Faculty Capacity and Support

The first has to do with capacity. Most faculty don’t have the technical expertise, the time, or the institutional support to manage their own WordPress installation or do anything more with OER than adopt a free PDF in place of their textbook. In fact, for many faculty, simply using a hosted WordPress site or uploading a free PDF into their LMS is beyond their technical capability, available time, and institutional support.

Do you find that hard to believe? According to the American Association of University Professors, in Fall 2011 41.5% of all instructional staff in US higher education were part-time (adjuncts) and another 19.3% were graduate students. They made up more than 60% of US instructors in higher education. Generally speaking, these instructors are overworked, poorly paid, and poorly supported. When you add in the 15.7% of instructional staff who are full-time, non-tenure-track faculty, the total number of contingent instructional staff in the US reaches 76.4%. These contingent faculty likely teach four or five courses a term – or teach a different class at three different institutions each semester. They do not have the technical expertise, the time, or the institutional support to engage meaningfully with OER.

On a related note, my experience in talking with thousands of faculty in my two decades of advocating for open content has been that the more at-risk students a faculty member is serving, the less likely she is to have technical expertise, time, or access to institutional support. In other words, the faculty in the position to make the biggest difference in students’ lives through OER are the faculty who are most likely to struggle to do so.

If these faculty are to help students realize the potential benefits of OER – which go infinitely beyond offering them a free PDF – they need support. For many contingent faculty, as well as other faculty at severely under-resourced institutions, value-added services from outside the institution may be the only support available to them. I wholeheartedly agree that the contingent faculty situation needs to be addressed in a coherent, systematic manner, and I am glad that there are people working on that issue. But while that important work is being done, faculty need support now. Value-added services are a reasonable way to do provide that support. And with support, they can do amazing things.

Interaction and Learning

The second reason these value-added services are important has to do with student learning. When I listed the things faculty lack above, you may have noticed I omitted pedagogical training, knowledge of basic learning science, or an understanding of instructional design principles. (I omitted these above since I planned to mention them here.) It is widely understood that faculty receive little or no training on these subjects (implying a belief on the part of our institutions that a terminal degree in your discipline will somehow make you an effective teacher – but that’s a subject for a different blog post). Contingent faculty (who, remember, comprise over three quarters of all instructional staff nationwide) are even less likely to receive this kind of training or support than their tenure-track peers. And again, the faculty who serve our most at-risk students are the least likely to receive training or support in these areas.

If you haven’t been trained in learning science or instructional design, uploading a free PDF to your LMS may sound like a great way to use technology to engage students. And to the extent that some proportion of your students would have foregone purchasing a traditional textbook, this will increase student access to learning materials. But this strategy only uses technology to replicate what we could already do with printed books – facilitating the reading of static words and images.

Interactivity – when well designed – can lead to huge gains in learning beyond reading static materials or even using multimedia resources (like watching a video). I think it is generally agreed that we learn by being actively engaged in “doing” more than we learn from passively watching a video or reading a page of text. But in case you are unconvinced, let’s look at a paper by Koedinger, McLaughlin, Jia, and Bier’s titled, Is the Doer Effect a Causal Relationship? How Can We Tell and Why It’s Important from LAK16. In this paper the authors examine the impact of “doing” on thousands of students in several courses. Students in all courses had access to openly licensed readings and interactive activities from Carnegie Mellon’s Open Learning Initiative. Students in some courses also had access to lecture video. The research presented in the paper examines the effect on learning (as measured by quiz grades and final grade) of using these different types of resources. Readings and lecture videos are fairly straightforward formats to understand. Gratefully, the authors describe the “interactive activities” in the courses in some detail:

Interactive activities are aligned with course learning objectives and are embedded in the course content. They provide opportunities for students to test their understanding of concepts and to practice skills. Such learning opportunities take various formats (e.g., multiple choice questions, interactive simulations, drop and drag, matching, and other options) and deliver immediate tailored feedback as-needed (e.g., when a selected answer is incorrect) or as-requested (e.g., in the form of a hint). Many activities are multiple-choice questions, but others, like those shown in Figure 1, provide other forms of response selection (1a) and response construction, including the open-ended submit and compare (1b). In all cases, students have immediate access to correct responses.

What did the authors find?

As shown [in Table 5 in the paper], the doer effect is consistently observed. The standardized coefficient of the effect of doing [using the interactive activities] on outcomes is always significant and much higher than the standardized coefficient of the effect of reading (not always significant). The ratio of the size of the doing to reading effect goes from 2.2 to infinity (because in one case, quiz score in Statistics, the reading effect is not positive) with median of 6 — the same ratio we found previously! In other words, the effect of doing [using the interactive activities] is generally about 6 times greater than the effect of reading across four different courses and involving over 12,500 students. (emphasis added)

OER-as-free-PDF, or even OER-as-affordable-printed-text, increase access to core materials and can be associated with course-level gains in measures of learning and success (like grade and completion rate) because more students have access to the materials they need. But free static resources are no more or less inherently effective at supporting individual student learning than their more expensive static counterparts – because both fail to support meaningful interaction.

But weren’t we supposed to be discussing value-added services, you might be wondering? What’s the connection between interactive activities and value-added services? Interactive activities of the kind described by Koedinger and his colleagues can be created, managed, shared, and used only in the context of a platform. Faculty who struggle to use hosted WordPress are not going to host these kinds of platforms themselves. Institutions that outsource hosting of their learning management systems aren’t going to host these kinds of platforms internally. Consequently, the only way these kinds of platforms are going to be used is if people or organizations provide value-added services around them.

Humans Can Interact with Each Other, Too

I pause here to make a few observations, borrowing Moore’s (1989) framework identifying three types of interaction. The Koedinger-style in-situ activities support student – content interactions and have the benefit of providing an essentially infinite amount of practice with immediate feedback. It’s also worth noting that the permission to engage in the 5R activities granted by OER make entirely new categories of student – content interactions possible. But as Moore suggested, interactions don’t have to take the form of student – content interactions. Student – student interactions and student – teacher interactions can also be deeply meaningful. These interactions have other benefits, including the building of trust, confidence, encouragement, and connection between human beings. However, supporting these interactions among large-ish (10+) numbers of people in ways that will improve their learning is incredibly difficult without the help of platforms.

One of my favorite platforms for supporting meaningful student – student interaction (though this will show my age) was Fle3. Fle3 was, among other things, a structured discussion board that required students to categorize their messages and would only allow certain types of messages to be posted in response to other types of messages. These features encouraged student discussions to develop along an established model of progressive inquiry, rather than meandering aimlessly as conversations on generic discussion boards are wont to do. Here’s an example of what that looked like in Fle3:

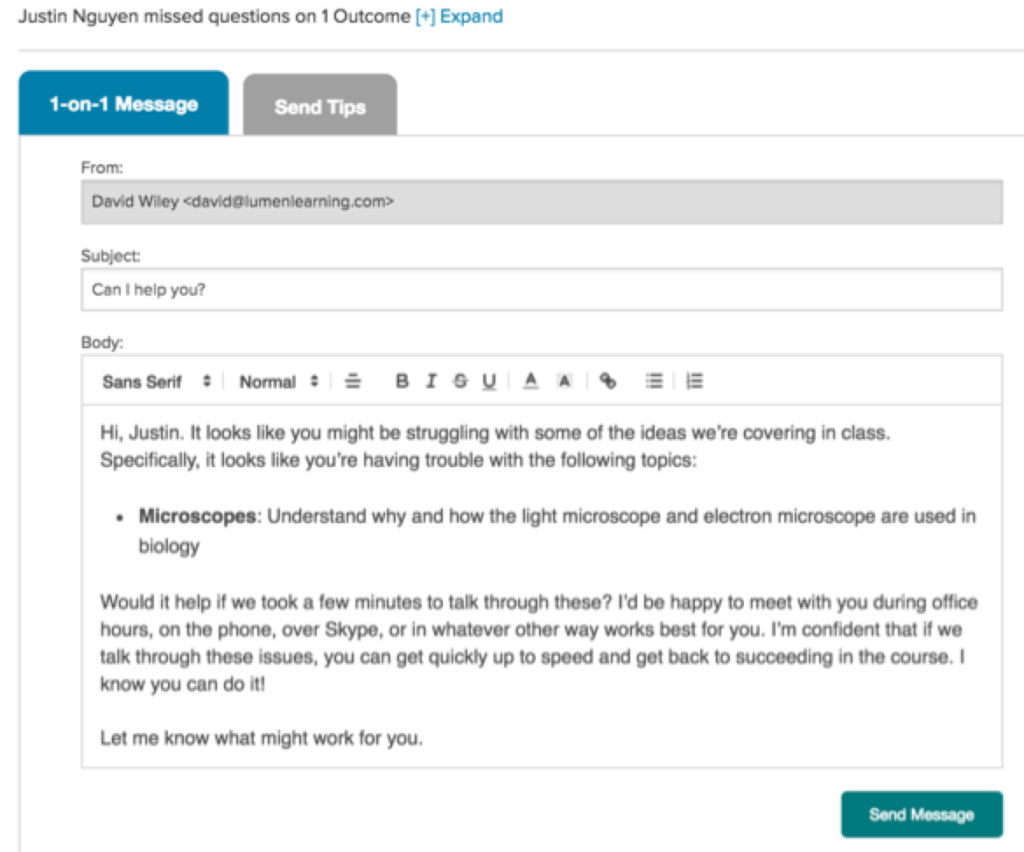

One of my favorite platforms for enabling student – teacher interactions (though I will admit I’m biased here) is Waymaker. Waymaker contains a set of semi-automated messaging tools that help faculty see which students need their help, and then send them each an individualized invitation to meet during office hours or talk over Skype. The message includes a list of the specific topics the student is struggling with (based on their performance on formative and summative assessments, whose items are each aligned to specific learning outcomes) so that their conversation can begin with a focus on those areas. Here’s what that looks like:

Let me further pause to acknowledge that yes, your campus already has an LMS, which is a platform. And no, your LMS does not offer support for Koedinger-style, or Fle3-style, or Waymaker-style, or any of the infinite variety of novel student – content, student – student, or student – teacher interactive activities you might want to create, manage, share, and use. Your LMS is a very serviceable integration point where these platforms can be brought together in a coherent whole using LTI, but your campus LMS “is not the droid we’re looking for.” Arguing that your LMS supports all the interactive activities you could ever want to use in support of learning is like arguing that a free PDF provides all the benefits you could ever want from OER.

Concluding Thoughts and the Future of OER

Some of the value-added services offered in conjunction with open source software or OER add very little – if any – value. I haven’t called those out by name here. But there are many which do add significant value, and I’ve listed some of them above. I’ve then described one family of such value-added services – namely platforms that make a wider array of student – content, student – student, and student – teacher interactions available in the context of OER.

It’s easy to get caught up in a means-ends confusion when it comes to OER. Too often our advocacy for OER adoption loses its way and becomes advocacy of OER adoption for the sake of OER adoption. Our once expansive vision of the end goal contracts to simply saving students money, and in that context OER-as-free-PDF is an acceptable solution. And it’s this kind of thinking that I have worried will destroy our movement since 2012. (If you haven’t read this short post, you might consider doing so. My concerns have changed very little in the last 5 years.)

I believe that improving student learning has to be the end goal of everything we do. When we keep that end firmly in mind, the reason we advocate for OER becomes “to enable drastically better student learning while saving students money.” OER adoption is a means to the end of deeper student learning – not an end in itself.

Keeping the goal of deeper learning firmly in mind leads to a range of critically important questions. How can we combine current (generally static) OER with well-designed interactive activities (which, when openly licensed, are also OER)? How do we change the thinking of the OER movement so that OER is no longer synonymous with static content? How do we unleash the full power of OER in the context of the platforms necessary to create, manage, share, and use the interactives we know support better student learning? How do we ensure that interactive activities increase, improve, and strengthen human relationships (student – student and student – teacher) rather than subverting or replacing them? How does the research on interactive activities relate to emerging work on OER-enabled pedagogy (which contains its own unique implications about the platforms necessary for revising, remixing, and redistributing OER)? How can traditional and OER-enabled approaches be combined in a way that will support deeper learning than either approach individually?

Honestly, these are some of the toughest questions I struggle with individually as I worry about the future of the movement. They’re also among the hardest questions we wrestle with in our work at Lumen. But my purpose in writing isn’t to convince you that Lumen’s approach to answering these questions is the best approach. My purpose in writing is to persuade you that these questions are critically important to the future of the movement and to get you thinking about how you will answer them. If nothing else, I hope to help you remember that OER adoption is a means – and not the end. Because a future in which OER-as-free-PDF – “unadulterated by the stain of platforms and other value-added services” – competes against new offerings from publishers that provide a broad range of interactive activities (and support for faculty), is a future in which there won’t be many people using OER.

I’ve said before and will say again – It’s 2017; we have learning management systems that can house free OER and provide all of the things described as added values in the Lumen model. A learning management system (LMS) allows faculty to create any kind of in situ assessment they want to create. An LMS has analytics to gauge where students are in the learning journey. The specific example mentioned about including a prompt to meet via Skype is easy. All of the ‘packaging’ is available in an LMS. All of the ‘added value’ for which Lumen is charging recurring fees could be included in the free OER license. I think rather than me asserting that this is possible with an LMS and David continuing to assert that only a Lumen type (for-profit 3rd party) platform can do “the infinite variety of novel student – content, student – student, or student – teacher interactive activities you might want to create, manage, share, and use,” I would like to figure out a way to test what is possible with either method.

Ultimately, though, it’s not about the tools, but about how faculty and students are best supported. If an institution can’t get it together to support their faculty to learn how to Manage the Learning in their System, then it might be practical to hire that support from a 3rd party. That is, however, not an optimal scenario for strengthening a faculty or promoting deeper learning opportunities that are based on strong faculty – student relationships. “Enabling drastically better student learning while saving students money” is not a peripheral activity.

I fully agree that OER-as-free-PDFs is a future that we can and should avoid.

> I’ve said before and will say again – It’s 2017; we have learning management systems that can house free OER and provide all of the things described as added values in the Lumen model.

Dan, you don’t understand Lumen’s model or offerings, and consequently shouldn’t make claims about “all of the things” in Lumen’s model. Each time you do, you’re wrong.

> A learning management system (LMS) allows faculty to create any kind of in situ assessment they want to create. An LMS has analytics to gauge where students are in the learning journey. The specific example mentioned about including a prompt to meet via Skype is easy. All of the ‘packaging’ is available in an LMS. All of the ‘added value’ for which Lumen is charging recurring fees could be included in the free OER license.

One of the primary services we provide as part of the recurring fees you mention is ongoing faculty support. In the last two months alone we’ve resolved over 1,000 support tickets from faculty with a 98% satisfaction score and median reply time of 5 hours. These tickets include everything from help finding additional OER and supplemental materials to technical support issues. Obviously you can’t put a “free OER license” on this kind of support. You do not understand Lumen or our model, and you need to stop making false and irresponsible claims about “all of the added value for which Lumen is charging.”

> I think rather than me asserting that this is possible with an LMS and David continuing to assert that only a Lumen type (for-profit 3rd party) platform can do “the infinite variety of novel student – content, student – student, or student – teacher interactive activities you might want to create, manage, share, and use,” I would like to figure out a way to test what is possible with either method.

I think this kind of test is meaningless for reasons I will describe below. But since you’ve asked for a way to conduct such a test, I suggest you simply reimplement the three examples described in this post in the major LMSs. Actually, to make the task significantly easier and faster, I invite you to implement these highly simplified versions of the three interactives described above using only the capabilities that exist within major LMSs:

* Koedinger-style student – content interactives. Embed a machine-graded assessment item directly within a page of content. Don’t link to the item, but embed the practice opportunity directly within the page of content (like you would embed a YouTube video) so that students truly have access to the practice opportunity in situ.

* Fle3-style student – student interactives. Within the LMS’s discussion board, implement a simple taxonomy of three message types (e.g., argument, evidence, rebuttal) in such a manner that students are prevented from submitting a discussion post unless they have categorized their post as one of these three types. If this is easier to do using an LMS tool other than the discussion board, feel free to use another approach.

* Waymaker-style student – teacher interactives. After students have taken each machine-graded assessment, automatically generate an email to every student that includes a bulleted list of the learning outcomes aligned with each item they missed on the assessment.

So there’s a test – reimplementing three miniature versions of capabilities that exist today in non-LMS platforms (but can be easily integrated into the LMS via the open LTI standard). But here is why this or any other test is meaningless. I’m arguing that “people and organizations can imagine and create novel platforms that provide an infinity of capabilities beyond what the LMS offers.” You, by disagreeing, are arguing that “there is literally no capability that can be imagined and provided by a novel platform that is not already provided within the finite capabilities of an existing LMSs.” That statement is obviously logically false.

> Ultimately, though, it’s not about the tools, but about how faculty and students are best supported. If an institution can’t get it together to support their faculty to learn how to Manage the Learning in their System, then it might be practical to hire that support from a 3rd party. That is, however, not an optimal scenario for strengthening a faculty or promoting deeper learning opportunities that are based on strong faculty – student relationships. “Enabling drastically better student learning while saving students money” is not a peripheral activity.

I agree that enabling drastically better student learning while saving students money is not a peripheral activity. Yet there are many core – or “non-peripheral” – activities around which institutions rightly choose to partner with third parties. Inasmuch as providing students with access to their core learning materials is what we’re talking about, a specific example of this principle would be that colleges don’t own and operate the printing presses that produce the tens of thousands of printed textbooks their students are required to use each semester. A slightly more modern example would be that they generally don’t host and manage their LMS, either. Organizations and companies partner on core capabilities all the time, and whether or not this is optimal is highly dependent on what you’re trying to optimize for.

Thanks for the continued exchange, David. I never claimed (whether you use quotation marks or not) that “there is literally no capability that can be imagined and provided by a novel platform that is not already provided within the finite capabilities of an existing LMSs.” As you stated, That statement is obviously logically false.

I am arguing that there is literally no capability that can be imagined and provided by any platform that could not also be provided by an LMS. Learning management systems are not static things that never change, even though they may feel like that to some faculty at some institutions. It is certainly possible that some features might be more practically provided via a 3rd party, especially for a short period of time if that capability needs to be developed by the commons while some private enterprise retains control of ‘their’ feature. But, determining the practicality of providing any feature or process either ‘in house’ or via a 3rd party is something that should, IMO, be primarily a pedagogical, or androgogical, decision. My tendency is always to bring the decision back to the faculty – student relationship and to have an abiding faith in the power and purpose of innovating for the common good.

Then we’re in total agreement on this point – a hypothetical future LMS *could* include any capability, but today’s specific LMS has only a finite, limited set of capabilities.

An LMS is like an operating system – a future version of Windows *could* include any capability Microsoft desired to include. The same for OS X and Apple, or Ubuntu and Canonical. But we are all *greatly* benefited by the breadth and variety of applications written by third parties that are available for our operating system of choice. It would be a dismal world indeed if the only capability your computer had was what the operating system provided when you first turned it on.

I have found that the applications that come built into the operating system are seldom as good as those made independent of it. Microsoft Edge and Mozilla Firefox would be one example. MS Paint and Photoshop would be another. Wordpad and MS Word would be another. Coming back to the specific context of the LMS, there’s no LMS-provided discussion tool as good as Discourse. There’s no LMS-provided blogging tool as good as WordPress. There’s no LMS-provided wiki tool as good as Mediawiki. &c.

If I’m understanding you correctly, our disagreement in this conversation lies in our ambitions for the LMS. I believe the ability to draw in creativity and innovation from a wide range of sources in support of teaching and learning is important, and not only “for a short period of time” while we wait for LMS vendors to create a watered-down clone. I have a strong preference for modularity, interoperability, and a healthy ecosystem of competing ideas and pedagogical models. In order for this ecosystem to exist and function, the LMS’s proper role must be that of an operating system where the LMS provides a base of core functionality and that people will, depending on their needs and desires, install additional (LTI) applications.

And I believe that LMS vendors share this vision of the LMS as an OS – I’m not sure how else you could explain the significant time and expense they have invested in creating and implementing the LTI standard, whose sole purpose is enabling this ecosystem of third party applications.

I’ve thought more about those features that might be more practically provided via a 3rd party. I’m a long time fan of VoiceThread (I’ve used it in 3rd grade classrooms and MBA programs successfully, although, the MBA faculty were much slower on the adoption than 3rd graders.) I don’t see any LMS duplicating the capabilities of VoiceThread anytime soon, and there’s not much reason to because VoiceThread’s LTI integration works very smoothly. I like the Big Blue Button. I’m really intrigued with H5P. Intelliborad is leading the way with competency tracking and reporting. The group above do things that won’t practically be incorporated into most LMSs anytime soon.

Then, there are a class of what I call higher ed institutional/program assessment report generators; an example of that would be the LiveText-Taskstream-Tk20 conglomeration. This class exists, still, due to the inertia of higher ed program administrations in general. There is, also, a rapidly growing group of ‘learning analytics’ providers that attach themselves to various points of the learning continuum almost randomly, it seems. LMS vendors are at various places in this development. The learning analytics that Lumen does is appropriately attached, as far as I can tell from my woefully limited knowledge of that magical platform.

I do think you’ve correctly identified our disagreement in this conversation as our ambitions for the Learning Management Systems of our public learning institutions. I want faculty and students to have as much ownership and authority as reasonably possible of the systems that manage learning.

This discussion is reminding me of my time in the days of pre to post monopoly telecommunications which I referenced here http://developingprofessionalstaff-mpls.blogspot.com/2013/01/if-youre-teacher-youre-leader-part-2.html . In those days, AT&T was asserting that nobody who worked for somebody other than their corporation was ever going to be able to understand or securely provided the complexities of their ‘natural monopoly.’ About 10 years after the time referenced in the linked post, AT&T paid me some substantial money to do some work for them. Their Help Desk system was actually quite good; other pieces of the org, not so much. But, then, I’ve been accused of not being very good at making money for people who don’t need it.

> I do think you’ve correctly identified our disagreement in this conversation as our ambitions for the Learning Management Systems of our public learning institutions. I want faculty and students to have as much ownership and authority as reasonably possible of the systems that manage learning.

This statement implies that I disagree that faculty and students should have as much ownership, authority, and control as possible over the systems they use to enable and manage learning. My entire argument – that we need a thriving ecosystem of extra-LMS components that can be integrated via LTI – is exactly the argument that faculty and students should have as much autonomy, control, and choice over the systems they use as possible. I’m not sure where you’re saying a disagreement lies.

Thanks David, you ask many good questions.

You made reference to the recent announcement made by Cengage and a few readers may be seeking additional info, here are a few link that may be useful:

Website – OpenNow – Institutional Learning Solutions – Cengage _ http://www.cengage.com/institutional/opennow

Article – Cengage offers new OER-based product for general education courses _ https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/10/10/cengage-offers-new-oer-based-product-general-education-courses

Blog – The Future of OER is Now _ https://blog.cengage.com/the-future-of-oer-is-now/

Presentation _ https://www.slideshare.net/jonmott/cengage-oer-and-learners-80789697

Phil Hill blog [2016] – About That Cengage OER Survey _ http://mfeldstein.com/cengage-oer-survey/ – with link to Cengage White Paper