Long-time readers will be familiar with “learning objects” and the “reusability paradox.” If you’ve been working in educational technology since the 1990s, you might want to skip the first section below. Or you may find it a sentimental walk down memory lane.

Learning objects and the reusability paradox

A learning object is “any digital resource that can be reused to support learning” (Wiley, 2000), and the goal of the learning objects movement was to design learning materials that were sufficiently small and self-contained as to be easily reused across many different learning contexts. Remember the joy of digging into a bin of Legos, pulling out random pieces and assembling them into whatever your heart fancied? This was the promise of learning objects, which were compared to Legos in almost every conference presentation and journal article on the topic.

The reusability paradox describes a difficulty at the heart of the learning objects idea. Here’s how I described it in the late 1990s:

1. The “bigger” a learning object is, the more (and the more easily) a learner can learn from it. For example, there’s only so much you can learn by studying a single photograph of a mountain (an image is a “small” learning object). On the other hand, you can learn quite a lot from a chapter on mountain formation, with multiple images, animations, and explanatory text (a chapter is a “large” learning object).

2. The “bigger” a learning object is, the fewer places it can be reused. For example, a single image of a mountain can be placed into a wide range of learning materials (e.g., it could be embedded in chapters about geography, history, photography, etc.). On the other hand, there are only so many places you can reuse an entire chapter on mountain formation.

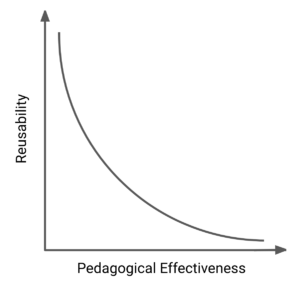

To state it briefly, there is an inverse relationship between reusability and pedagogical effectiveness.

Because pedagogical effectiveness and potential for reuse are completely at odds with one another, the designer of learning objects faces a difficult choice. They can either (1) design smaller objects that are easier to reuse but require significantly more effort and assembly on the part of the instructor before they are useful for learning, or (2) design larger objects that more effectively support learning but have limited potential for reuse.

(If you’ve ever thought my writing was insufferably pedantic before, I promise you ain’t seen nothin’ yet. Try this detailed elucidation of the reusability paradox from 2002.)

The modern reader will no doubt scratch their head and ask, “why not just start with a larger, more useful learning object and adapt it to meet your needs?” The answer, of course, is that in the late 90s and early 00s the open content movement was only just beginning. We didn’t have the 5Rs back then. The book on learning objects I linked to above was published under the Open Publication License because Creative Commons didn’t even exist yet. The universal (and universally true) assumption was that learning objects were traditionally copyrighted, meaning you had to reuse them exactly as you found them (just like Legos).

OER and the Revisability Paradox

That bit of history prepares us to discuss open educational resources (OER) and the revisability paradox.

Open educational resources are teaching, learning, and research materials that are either (1) in the public domain or (2) licensed in a manner that provides everyone with free and perpetual permission to engage in the 5R activities. I don’t believe readers of this blog need much additional context about OER.

The revisability paradox describes a difficulty at the heart of the OER idea. Here’s my current best attempt at explaining it:

1. The more research-based instructional design is embedded within an open educational resource, the more (and the more easily) a learner can learn from it. For example, there’s only so much you can learn by reading an explanation of what a conifer is (a “simple design” OER). On the other hand, you can learn quite a lot from an activity that (1) isolates and explicitly describes the critical attributes that separate instances of conifers from non-instances and (2) provides you with the opportunity to practice classifying trees as instances or non-instances, coupled with immediate, targeted feedback (a “research-based design” OER).

2. The more research-based the instructional design of a OER is, the harder it is to revise and remix without hurting its effectiveness (that it, the more instructional design expertise is necessary to revise and remix effectively). For example, many different kinds of changes could be made to a simple explanation of conifers without changing its effectiveness in supporting student learning. On the other hand, there are many ways of changing the research-based design that would cause it to be no more effective than the simple explanation.

In essence, without instructional design expertise, looking at well designed learning resources is like watching a sporting event whose rules and nuances you don’t understand. Remember watching hockey/baseball/soccer/cricket for the first time? Remember the first time you watched with someone who deeply understood the game, and you started to realize how much you were missing – even though you were both watching the same game? It’s like that, but with the research on supporting learning effectively. Without instructional design expertise it’s easy to look at something like the explicit isolation of critical attributes and think “Boring! I have a way more interesting way of explaining that!” …and we’re right back to explaining.

In other words, there is an inverse relationship between revisability and pedagogical effectiveness.

Implications

One of the amazing things about the OER movement is how the “OER way of thinking” has democratized access to the creation of learning materials. Anyone with domain expertise and a word processor or WordPress instance can write definitions, descriptions, and explanations. This won’t result in particularly effective learning materials, but it will result in OER that look a lot like their traditionally copyrighted counterparts, are less expensive than their traditionally copyrighted counterparts, and that anyone can revise or remix without doing any damage.

Revising or remixing OER with a research-based instructional design is much more like playing Jenga blindfolded. When you don’t fully understand the instructional functions of the different elements of the learning materials, there’s no way to know whether pulling one out or swapping it for something else or changing it in some other way will cause the whole efficacy tower to collapse. And the biggest problem, of course, is that when you destroy the efficacy tower you don’t know you did – because you don’t know the rules of the game and can’t really see what’s happening.

Choices… and a Question

The designer of learning objects can either (1) design smaller objects that are easier to reuse but require significantly more effort and assembly on the part of the instructor before they are useful for learning, or (2) design larger objects that more effectively support learning but have limited potential for reuse.

Likewise, the designer of open educational resources can either (1) create “simple OER” – resources with rudimentary instructional designs that aren’t particularly effective at supporting student learning but are easy to revise and remix without decreasing their effectiveness, or (2) create “complex OER” – resources using research-based instructional designs that are far more difficult to revise and remix without decreasing their effectiveness (i.e., they’re “easy to break”).

Which leads me to wonder… What is the role of instructional design / learning science / learning engineering / related forms of expertise in the creation – or revising and remixing – of learning materials? Insisting that this expertise is important feels like it pulls against the democratizing power of modern conceptions of openness in education. But denying that this expertise matters feels like it joins the broader anti-expertise chorus currently eroding public policy.

So… now what?

You must be logged in to post a comment.