Cable Green sent a frustrated email today to the Educause Openness Constituent Group. Here’s the key point:

The Babson Survey Research Group has released a new report: Growing the Curriculum: Open Education Resources in U.S. Higher Education.

This sentence is of particular concern to me: “One concept very important to many in the OER field was rarely mentioned at all – licensing terms such as creative commons that permit free use or re-purposing by others.”

I think I’ll run a webinar series (as many as it takes) for Chief Academic Officers to help them better understand: (1) OER and (2) the difference between “free” and “open.”

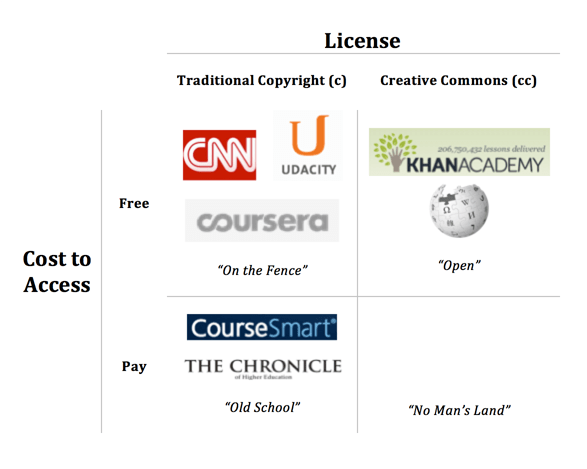

I share his frustration. Here’s one humble contribution to making it easier to understand the difference between free and open.

A word about each quadrant.

On the Fence. 99% of content on the internet probably falls into this category. Completely free for you to access and read, but fully copyrighted – no permission for you to republish NYT articles on your own website or translate that CNN article into Swahili.

Old School. A small but growing amount of online content fits this category, like the articles behind the Chronicle’s paywall.

Open. Free to access and read, with free permissions to do the 4Rs – reuse, redistribute, remix, revise. Like the videos in Khan Academy or the text in Wikipedia.

No Man’s Land. I’m not aware of anything in this space. The first person to purchase the material would start legally distributing it outside the paywall, defeating the purpose.

As I’ve been saying, the real risk of the On the Fence MOOCs (aka xMOOCs) is that they confuse people about “open.” “Open” does not “mean free to access but copyrighted,” like Udacity and Coursera are. Open means free access plus free 4R permissions. The On the Fence MOOCs are drawing energy and attention away from where the real battle is happening – in open educational resources. OER is the only space where everyone has permission to make and redistribute the changes necessary to best support learning in their local context. Consequently, OER is the only space where continuous quality improvement is possible, as I’ve been saying for years now. You can have all the analytics in the world telling you where your course needs improving, but without 4R permissions you’re not allowed to make those improvements.

Being open is key to driving quality, and we need to help Chief Academic Officers who are desperately trying to improve student success get the message.

The OER movement dug its own grave by focusing nearly all the the available funds on producing non-remix-able materials with CC licenses as if that were the end-all and be-all. Instead of complaining how the xMOOCs are taking attention away form OER – perhaps OER should actually do something relevant and by those efforts once again become relevant to the future of education. Open is not open until it is remixable. Far too many companies and universities took money in the name of OER to produce non-remixable content as if that would somehow solve the problem. The problem is solved when something is open enough to create a dynamic self-sustaining ecology that grows naturally and virally.

I agree. And “remixable” does not necessarily mean free either.

I believe Flatworld Knowledge will be in “No Man’s Land” after January 1, 2013, if they retain CC licensing. If not, then they are old school, of course.

Why is that? There is a lot of power and benefit in their self-editing technology, empowering instructors to derive changes that improve their teaching. They use a CC-NC license. Changing that to “all rights reserved” would necessarily eliminate that feature.

FWK is still the best bargain in QUALITY textbooks out there. Their content is easily as good as most (far more expensive) commercial textbooks, and FAR better than most OER content.

FWK will be fine. If not, then their model will “fail forward”. FWK has forever impacted the commercial textbook publishing industry, in a way that benefits consumers. That’s more than I can say for OER – especially “CC-BY” OER – which to date has been a funding black hole, with not very much to show for results.

I can think of at least 3 instances of CC/Pay. Jonathan Coulton’s music – CC-licensed but have to pay to download. Cory Doctorow – CC licensed by can be bought and Bloomsbury Academic – a publisher selling books under CC and also distributing them online.

Not necessarily content, but no-man’s land would include GPL open source software that is for sale commercially; for example, companies making GPL WordPress plugins, selling them and then customers distributing or modifying them is perfectly legal if the license remains in tact.

David,

How confident are you that increased openness will result in higher quality? Is this what you mean by “being open is key to driving quality?”

Fallacy #1: “Being open is key to driving quality”

So all the really great “all rights reserved” content (fiction, textbooks, films, etc.) would/could be made better in “open” (CC-BY) environments?

How about we compare the most open environments (within the OER space) to those where some rights are reserved (like CC-NC) and “all rights reserved”? Look at the results, in USE. The results stand for themselves.

I’m not saying that one can’t have quality open materials, but open is not a “key to driving quality”. In fact, in the current OER environment, quality is one of the most glaringly missing factors. Why? Because academicians are not used to working in an environment that has close tolerances for failure. If your OER project doesn’t work, you don’t get fired – you just start doing something else (like teach, or administer) or apply for another grant.

Fallacy #2: …”and we need to help Chief Academic

Officers who are desperately trying to improve student success get the

message.”

CAO’s on most university campuses are so behind the curve it isn’t even funny; and that doesn’t include the structural problems that are built into academic culture that mitigate AGAINST their deploying OER solutions in the first place (assuming those OER solutions are as good or better than the alternatives, which they are most decidedly not, yet). For one thing, instructors are able to use whatever materials they want. What does a CAO have to do with anything?

The only way to make OER work is to create GREAT OER content – something that, so far, seems to have eluded even the most well-funded OER program/projects. Why is that the case? See my answer to fallacy #1.

Education costs too much, and so do the materials – like textbooks – that people use to supplement their education. OER is one solution, but others are fast arriving on a technology train that can’t – and won’t – stop. The conductors on that train are people who fully understand that if they don’t effectively deliver their payload at a cost that people can afford, and want to use, they are going to have to look for another job. That’s the kind of mentality that academia doesn’t have, at least not at senior and intermediate faculty/administrative levels. Thus, the bruise that begins to rot the academic peach.

Good post faze – you hit the nail on the head. Quality is critical and without sufficient quality in version 1, there is never any incentive to produce version 2 so the argument about continuous improvement does not come into play. See my argument at http://edtechnow.net/2012/03/31/learning-analytics-for-better-learning-content/.

Nor can quality be legislated for – you need some sort of selection process to winnow out substandard products. OER programmes which are funded by government on the supply-side do not have this vital winnowing process – which is why they will never produce the quality that is required.

It’s not pay to access but would CC licensed kickstarter or unglue.it projects be examples of No Man’s Land as a model?

Thank you for writing this post Sir. Onward with Openness.