There’s a great conversation – a debate, almost – occurring right now about two indisputable facts:

- The College Board recommends that students budget around $1200 per year for textbooks and supplies.

- Surveys of students indicate that they spend around $600 per year on textbooks.

How can there be a debate about facts which no one disputes? The debate is around which fact is appropriate to cite under which circumstances. See excellent contributions to the discussion by Phil Hill, Mike Caulfield, Bracken Mosbacker, Phil Hill (again), and Mike Caulfield (again).

When someone cites the College Board number, they often (but not always) do so in the process of trying to lead their listener to the conclusion that textbooks are too expensive. Not just really expensive. Too expensive. In the textbook context, too expensive means “so expensive as to be harmful to students.” The College Board number typically surfaces in an argument that runs along the lines of – textbooks are too expensive, thus harming students, and for the sake of students we should do something about the cost of textbooks.

When someone cites the student survey number, they often (but not always) do it in the process of reacting to the College Board number, as if to say “See? Textbooks aren’t nearly as expensive as some would lead you to believe. The situation isn’t that bad.” And, by implication, students are doing ok.

My question is this: if the issue we want to discuss is the impact of textbook costs on students, why don’t we just go straight to the data that deal directly with the impact of textbook costs on students? When we dip our toe in the $1200/$600 debate we’re likely to raise questions among listeners that will only distract them from the issue we’re actually trying to discuss.

Rather than using cost data as a proxy for impact on students, let’s talk about what the data say the actual impact of textbook costs is on students.

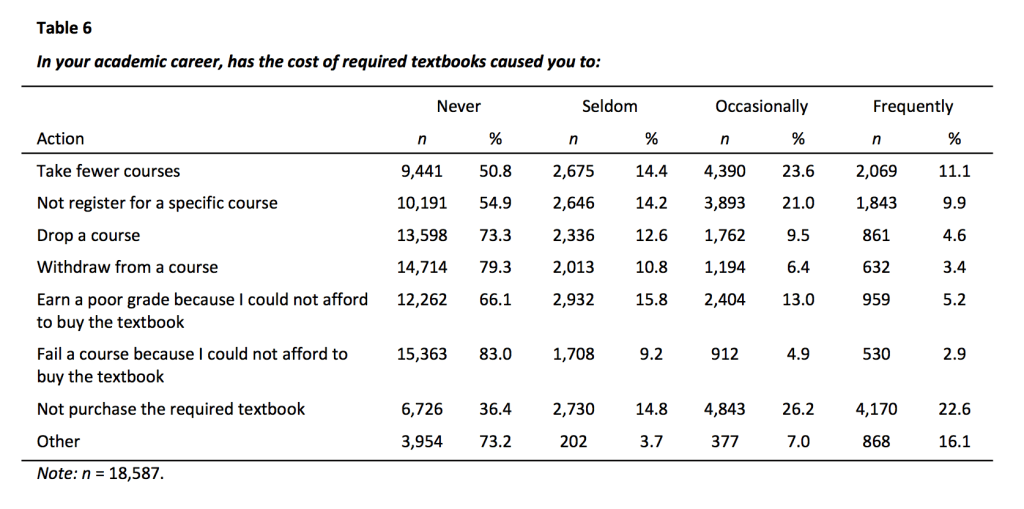

One of the best sources of data available on this subject are the Florida Virtual Campus surveys. The most recent, including over 18,000 students, asks students directly about the impact of textbook costs on their academic career:

What impact does the cost of textbooks have on students? Textbook costs cause students to occasionally or frequently take fewer courses (35% of students), to drop or withdraw from courses (24%), and to earn either poor or failing grades (26%). Regardless of whether you have historically preferred the College Board number or the student survey number, a third fact that is beyond dispute is that surveys of students indicate that the cost of textbooks negatively impacts their learning (grades) and negatively impacts their time to graduation (drops, withdraws, and credits).

And yes, we need to do something about it.

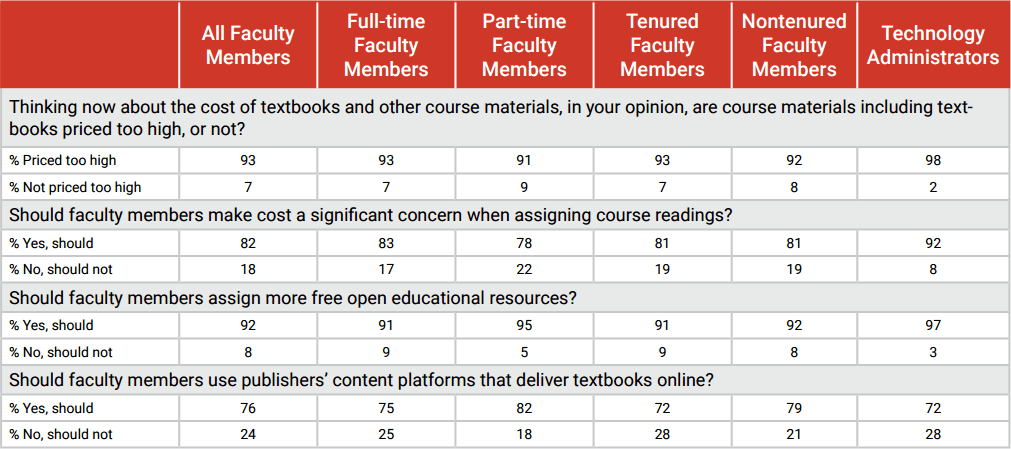

Thankfully, faculty are already well aware of the problem. According to a recent Inside Higher Ed / Gallup poll, more than 9 in 10 faculty agree that textbooks and other commercial course materials are too expensive:

According to the poll, faculty also overwhelmingly agree that OER are a viable solution to the problem of textbook costs: more than 9 in 10 faculty believe that they should be assigning more OER. Now we just need to help and support them as they make that change.

(Another very real impact of textbook costs on students is their contribution to student loan debt. That’s an important conversation, but one that I’ll save for later.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.